Cinema has never been based on anything less than illusion, yet few tools are as direct and physical as makeup. Even before digital effects could transform faces with a button press, makeup artists were already pushing human features into the territory of the grotesque, the beautiful, and the unimaginable. The radical changes in some of them made the viewers gasp, flinch, or even turn away. Not only has extreme makeup appalled the audience, but it has also redefined what a film can demonstrate: that a face can be as eloquent a storytelling tool as a single line of dialogue.

During the early years of practical effects, the basis of such transformations was frequently found in the most unlikely places, such as the techniques of the stage and experimental materials. Even a fox base that had been prepared carefully could make the difference between layers of latex and pigment sticking to the skin. This invisible base enabled artists to create faces that were disturbingly real and made the audience believe that monsters, mutations, and miracles were right before their eyes and not behind camera effects.

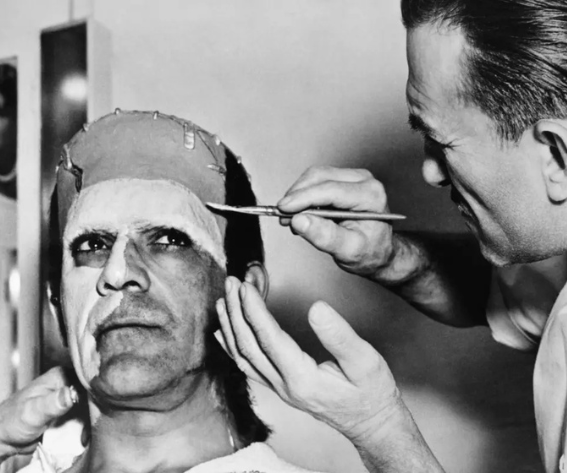

The Birth of Screen Monsters

Frankenstein (1931) was one of the first and most renowned shockers that came in 1931. The work of Jack Pierce on Boris Karloff produced a monster with a flat skull, bolts on the neck, and heavy-lidded eyes that became cultural icons immediately. The appearance was highly disturbing at a time when viewers were not used to such explicit changes. It was not just makeup as a decoration but makeup as identity. Karloff disappeared under the layers, and a monster was created.

This was a period that formed an essential rule that to this day remains. The more persuasively makeup takes the place of a human face, the more authority it can have to disturb. These early monsters were not scary since they were overdone, but they were realistic in their worlds.

Possession, Decay, and the Fear of the Body

The horror movie industry went way beyond suture and painted shadows several decades later. In The Exorcist (1973), the progressive possession of Regan was mapped out virtually all in makeup. Delicate discoloration, sinking wounds, and the last hideous face made a child unrecognizable. The last appearance was not the only shocking part but the gradual, realistic fall. Every step was medically realistic, which contributed to the supernatural aspects being even more terrifying.

The Fly (1986) by David Cronenberg was perhaps the film that redefined extreme makeup more than any other film. The metamorphosis of Brundlefly, played by Jeff Goldblum, is one of the most torturous physical trips ever to be shown on film. Teeth are lost, skin is scaled off, and limbs are twisted. The make-up does not immediately go to monstrosity. It documents decay. The shock was not only in the imagery but also in the length of time that the camera stayed and made the viewers look at the vulnerability of the human body in such detail.

When Uncertainty Turns into Terror

Eraserhead (1977) provided another form of extremity in the psychological shock. The sculpted and carved deformed baby, done in an unexplained mixture of both sculpturing and organic materials, is one of the most disturbing designs in the history of the film. The way it was made is still being debated by viewers. The shock is based on ambiguity. It looks alive, yet unnatural. It cannot be categorized, and that is why one cannot be able to emotionally distance him or herself.

In this case, makeup does not work with gore but with uncertainty. The viewers do not know what they are viewing, and that confusion is the cause of fear.

The Golden Age of Changes

The 1980s was the golden age of practical effects, with filmmakers trying to outdo one another in magnitude and intensity. The transformation scene in An American Werewolf in London (1981) left audiences astonished, and it has never been matched. No cutaways are spared to the viewer. Bones lengthen, snouts burst out, and hair sprouts out of skin. The shock lies in the realism. It is not a symbolic transformation. It is a biological process that is going on in reality.

This era demonstrated that extreme makeup could be used to carry with it whole sequences without using editing tricks. The spectacle itself was the transformation.

Creating New Species

In fantasy films, the shock can be as simple as the sheer wholeness of a new race. Planet of the Apes (1968) established an early precedent, but the reboot trilogy of the present day elevated it. Although digital augmentation contributed to it, the underlying prosthetic designs created believable anatomy and texture. What disturbed viewers was not the fact that the apes were monstrous but that they were almost human. The boundary between species became indistinct in the most awkward manner.

Fantasy extreme makeup is not necessarily meant to repel. It is shocking at times because it makes us see ourselves in strangers.

Facing Historical and Physical Suffering

Historical horror has also been presented to audiences through extreme makeup. The cruelty that was meted out on Christ is depicted in The Passion of the Christ (2004) in detail. The film is divided into layers, reopening and deepening wounds throughout the film. The experience was physically challenging to a number of viewers. The makeup is not stylized. It is clinical. It is not meant to be a spectacle but a confrontation.

The Whale (2022) provided a shock of another type in more recent years. The fact that Brendan Fraser was able to become a severely obese man was based on a lot of prosthetics that were used to not only make him look large but also heavy, moving, and strained. It was not a grotesque shock. It came from empathy. The audiences were brought to the physical reality of a body in crisis, and the makeup was a transition to that emotional space.

The Reason Extreme Makeup Is Still Important

The thing that makes all these examples unite is not a gluttony but a purpose. Extreme makeup is shocking because it shows us something we would not prefer to see. It reveals corruption, fragility, alienation, and suffering. It compels viewers to face bodies that are not within the commonplace standards. By so doing, it reminds us that cinema is not only a matter of escapism, but it is a matter of pushing the boundaries of what we are prepared to see.

With the rising strength of digital tools, practical makeup may appear to be in danger of becoming a forgotten thing. But the most outrageous gazes in the history of the film are too physical. Pixels still cannot match latex, silicone, pigment, and patience in convincing the audience that the impossible is true. Extreme makeup survives due to the fact that it is at the most fundamental level of the cinema. It alters the human face and thus it alters our perception of ourselves.

Leave a reply