‘I wonder if one day music will come through here. Maybe if I remember some. Maybe you could play it for me. I also wonder if my home wasn’t real. The beach wasn’t real…’, confesses the protagonist of the feature-length film we are about to review, titled ‘Lost in Time‘.

‘Lost in Time’ is directed by Henry Colin and written by Henry Colin and Paul Kimball. It tells the story of Leda, a woman who appears to exist in two different dimensions, struggling to distinguish between imagination and reality. It seems that Leda can’t recall her past in its entirety. She reimagines fragments here and there, but the context is lost on her. However, all that changes when Jane, Leda’s friend, pays her a visit. In the spirit of Christmas, Jane gifts Leda a book.

Sci-fi is not her cup of tea, but Jane convinces Leda that this book is different, and she should give it a chance. This moment creates a loop in which Jane revisits Leda as if it were the first time, but with each subsequent visit, Leda is closer to discovering the truth. Or, so it seems. Once she senses that her reality might not be the one she hoped for, Leda embarks on an odyssey to discover the truth, persuade Jane to reveal the nature of her existence, and regain her lost identity before it’s too late, even if that means never healing her core wounds. It doesn’t take long to acknowledge the qualities of the filmmaking process. The exposition throws the bait at the viewers effectively, while the first act sets the foundation for the key narrative aspects to develop. The devotion and passion demonstrated by Colin, Kimball and the entire team are evident. Incorporating various devices of film language and theory, they’ve managed to engage the audience without being obtrusive.

‘Lost in Time’ adopts the sensibility of Bergman’s ‘Persona’, and the Lynchian nightmare, aided by a Kafkaesque prison. In other words, there are many layers to .Lost in Time. that need to be approached from different directions to grasp them fully. That said, the complexity lends the film a rewatch value. More importantly, the storytellers don’t intend to reveal everything at once. They don’t take the viewers by hand, but rather leave them to experience the themes and interpret the concept on their own.

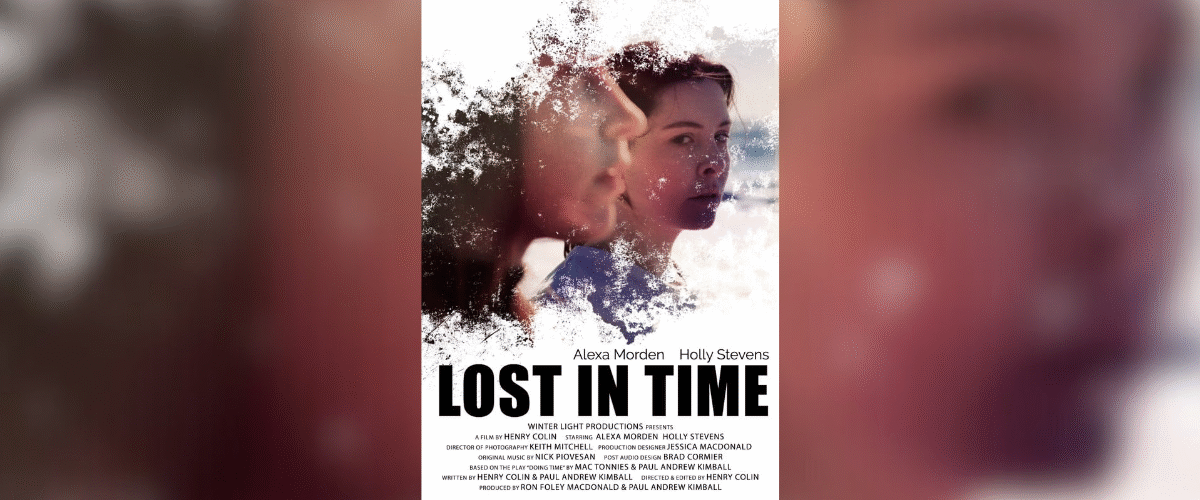

Alexa Morden and Holly Stevens, in the roles of Leda and Jane, respectively, have incredible chemistry on the screen. Being the only two characters who appear in the story, they carry the narrative on their shoulders solely. Leda is the leading protagonist, while Jane is the counterpart who challenges our heroine. Their roles change significantly. While Jane is the one who dominates the narrative and is the superior of the two in the first half, Leda takes over after the midpoint twist, provoking Jane to discover her epiphany, her calling. Both actresses rise to the occasion presented in front of them.

It’s not only about the lines they say, but their body language, their expressions, the mise-en-scene, and the juxtaposition (visibly noted during the prison sequences). Having a director who is comfortable working with talented actresses is the most significant strength of any project, and this is the case with Colin’s professional relationship with Morden and Stevens. Indie, auteur projects driven by a small cast are a director’s dream, and the results have been fantastic. Moving forward, it’s worth noting the cinematography. The film features two distinct visual styles, one for each of the protagonist’s worlds. Leda’s home has a charming, cosy vibe, rich with vibrant colours and production design, and supported by a white, heavenly light coming from the windows, which plants the seed for this world’s true meaning. On the other side is the prison – a dark, ominous place, where a small painting on a wall is the only thing that gives Leda hope.

Leda’s behaviour differs here – she’s exhausted, anxious and paranoid, completely opposite of Leda at home, where she’s calm, one with herself and fulfilled. The camera and lighting make sure to convey all these emotions and states of well-being that make the two protagonists feel more relatable, genuine and realistic. On top of that, the colour grading is excellent. It elevates the pre-existing palette of colours to make the most out of the settings. On the other hand, the impression is that the editing could’ve made the first act even more dynamic. It takes a while for the story to reveal the central dramatic situation and raise the stakes proportionally. The lengthy, uninterrupted shots could’ve been combined with short scenes where we see the protagonist doing different activities. Sometimes, the feeling is that the concept’s scope could’ve been broadened with more exteriors, and Leda having more agency. For instance, showing how Leda tries to escape the Kafkaesque nightmare would’ve allowed the second act to rely less on dialogue and more on plot points that put different challenges and obstacles in front of her.