The Brazilian government enacts a series of doubtful laws that allow condemned people not only to run free but also to run for leading political posts. An already corrupt system strengthens its position even more, determining Dr Quirinho’s mind – a famous lawyer – to break. Perceiving himself as Don Quijote, the lawyer is decided to take justice in his own hands. On his new journey around the system Dr. Quirino will meet Panca, whom he will identify with Sancho Panza and a prostitute, as Dulcinea. The main anti-hero becomes a corrupt important member of the government who campaigns for head of the state.

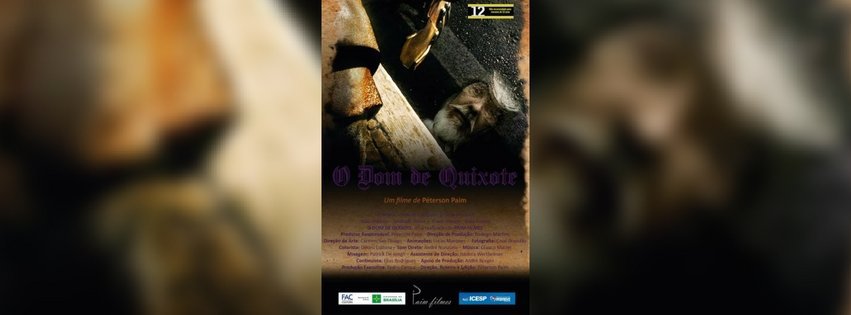

Peterson Paim’s story unfolds on the background of a law that cuts off education funds to cover budgetary deficit. Filmed on a personal tone – narrow shots and close-ups -, ‘The Gift of Quixote’ is a powerful critic addressed to the Brazilian society and especially its corrupt state leadership.

Dr. Quirino impersonating Don Quixote has a cynical flavour as if pointing one’s finger towards the corrupt and shouting ‘you’re killing Don Quixote!’. Of course, this is to be looked at in allegorical dimension: Don Quixote is a symbol of the power of imagination and fighting for one’s own convictions. After all, the power of imagination is well connected to one’s ability to shape their own ‘reality’ according to their dreams and aspirations, and is therefore a form of liberty and evolution as well – through one driving their actions towards achieving their future ideals, which every so often reflect things turned into better.

This great ability of dreaming and believing in a reality that might be slightly different from the actual state of things, is supported and fuelled by a relatively ‘sane’ environment that endows the lives of individuals inhabiting it with a certain level of psychical comfort. That threshold of comfort feels very far away, and distancing, in Peterson Paim’s film. At the same time bringing Don Quixote back to life is a sad way of saying that things have become so bad that trying to fight against them would be like fighting ‘against the windmills’.

There is black cynical sarcasm in ‘The Gift of Quixote’, whose gift is obviously his only way to detach from reality – to imagine his own reality. Also humorous on occasions, this short Brazilian film is lashing as much as it is bitter in its outcome; it is nevertheless an original enjoyable presence among short films, with a shy comic-book hue and a dim parody flavour; meaningful, genuine and entertaining.